What is

Dissenting

Social

Work?

Social Work Action Network protest Dublin 21st March 2014

According to the Oxford English Dictionary (OED), one definition of dissent refers to a disagreement with a ‘proposal or resolution; the opposite of consent’. The word and the actions or attitudes it hints at also signal a constellation of other words, such as resistance, subversive, dissidence and disruption. Dissent, maintains the OED, is likely to imply an alternative ‘proposal’ or ‘resolution’ that is at odds with the dominant or hegemonic way of responding to an ‘issue’, ‘social problem’ or set of circumstances. Perhaps reference to dissent also connotes an affective disposition, a mood or a vibe that is suggestive of an individual or a group seeking to ‘rock-the-boat’. Maybe dissent, as a number of Black feminist writers argue, can also find expression in anger intent on ‘setting things right’ and ensuring that there is social justice. Anger furnished a foundation for a progressive politics of dissent as illustrated by public sector strikes in Britain in 2023. Indeed, on the Left, wholly justified eruptions of protest and outrage might be characterised as displays of, what the Zapatistas term, digna rabia or noble rage.

In his eulogy to Marxist scholar and activist, Mike Davis (1946-2022), Palmer (2023: 51) observes that Davis ‘insisted that anger, so often considered a deforming lapse among those in intellectual circles aiming to make objective and judicious interventions, was a legitimate emotion, one capable of expressing, even driving, the necessary passion of research and writing, as well as informing a principled political opposition’. Palmer continues that ‘Mike was blunt in a 2020 interview: “What you need is a deep commitment to resistance and a fighting spirit and anger”’. Stephane Hessel, a former French Resistance fighter during the Second World War and subsequently one of the drafters of the UN Declaration of Human Rights, wrote of the need for ‘outrage’ in a world in which the earth was being despoiled, human rights obliterated and the gap between the super-rich and the rest of us was magnifying at an extraordinary pace. The ‘challenge’ then becomes one of trying to figure out how ‘to transcend from personal outrage to social influence and the rejection of the unacceptable through moral and ethical actions’ (Fronek and Chester, 2016: 165).

Moreover, collective political action is vital. The DSW project is rooted in the understanding that progressive social work practice and education can only be safeguarded if we set about creating new structures within the structures: new ideological and organisational formations that are wholly committed to waging a ‘war of position’ and creating new forms of radical ‘common sense’ (Hoare and Nowell Smith, 2005). I am not, though, so naıve as to believe that DSW is likely to become a majority preoccupation, but adherence to its main tenets could begin to detach sizeable and influential fractions which, in coalition with other movements in civil society, might have a significant and beneficial impact.

Around the time that neoliberal capitalism was beginning to gain a foothold in the U.S., Shirley Cooper (1977) maintained that social work is a ‘dissenting profession’. Writing in Australasia, almost half-a-century later, Patricia Fronek and Polly Chester (2016: 165) contend that social work is a ‘dissenting profession because in order to uphold its mission, social workers are agents of change obligated to address social injustice and breaches of human rights where they occur’.

Dissenting social work (DSW) is viewed as an approach intent on developing critical habits and habits of self-questioning. Relatedly, DSW interrogates dominant ways of understanding the social world within the discipline. It might, therefore, be interpreted as a form of neo-social work adding to those efforts bent on pushing back against moves to limit the field of possibilities for educators and practitioners. In starker terms, DSW contests the idea that educators and practitioners ought to serve as mere handmaidens or functional auxiliaries of capitalism and the institutional orders that it requires.

DSW, cannot be articulated along the lines of ‘blueprints’ or ‘action plans’, but it might be provisionally perceived as operating within a space patterned by, at least, a dozen themes, even commitments.

The defining themes of dissenting social work (DSW)

- DSW is attuned to and seeks to eradicate the harms caused to humans, other species and the planet by capitalism

- DSW is enriched by feminist perspectives and the theorisation of heteropatriarchy DSW combats white supremacy and racism and is alert to the dangers of fascism

- DSW tries to decolonise social work knowledge and to learn from perspectives derived from Africa, Asia and Latin America

- DSW recognises that social work has frequently been complicit in oppressive processes and nurtures a willingness to evolve forms of social work education and practice which challenge them

- DSW encourages analyses vibrating with an historical pulse and is keen to examine the evolution of economic, state and cultural processes marginalising, stigmatising or exploiting different groups

- DSW is future-orientated and dismissive of ideas implying there was a ‘golden age’ of benign social work existing before the arrival of neoliberal capitalism

- DSW appreciates the tremendous gains which technology brings, but is alert to the threats posed by techno-authoritarian

- DSW is rooted in critical social theory, committed to reading beyond the ‘set list’ and keen to emphasise the need for open debate on the future(s) of social work education and practice

- DSW is intent on critically interrogating ‘false trails’ and voguish theorists and theories often failing to adequately address core concerns impacting on social work

- DSW is convinced that dissent has to be a collective endeavour as opposed to an individual activity

- DSW is aligned with, energised, replenished and sustained by the oppositional activity generated ‘on the ground’ within trade unions, activist social movements, community organisations, progressive coalitions, ‘user’ networks, marches and campaigns

Clearly, these themes are far from exhaustive and these thematic points should be viewed as a foundation for discussion rather than a bombastic ‘manifesto’. Operating as interlinked coordinates, the themes merely aspire to provide a ‘thinking space’. Moreover, all of these points can, of course, be debated, refined, supplemented and even supplanted.

The final theme requires additional comment because the bedrock understanding in is that ideas alone cannot remake social work or the wider world in which it situated. In short, DSW is not rooted in philosophical idealism because it is recognised that changes in material practices, prompted and prodded by collective action, are vital. Ideas – modes of thought and how we conceive and ‘think about stuff’ – is of the utmost importance for progressive educators and practitioners because the ‘dissolution of a given form of consciousness’ can aid in the transition from one ‘epoch’ to another (Marx, 1981 [1857-58]: 540-41). For example, it might be argued that our current ‘form of consciousness’ and its associated lexicon and vocabulary is, perhaps unknowingly after four decades, ideologically marinated in neoliberalism. Consequently, critique within social work might include challenging aspects of the dominant vocabulary which bolster and reify – treat as things – certain ‘types’ of people or groups in society. This would involve contesting the use and validity of terms such as ‘welfare dependency’ which can be critically interpreted as a discursive product of specific economic and social relationships evolving during the neoliberal period (Garrett, 2018).

I perceive DSW as counter-posed to professionalism or rather what I prefer to refer to as a particular shaping of ‘professionalism’ within social work. Kathy Weeks (2011: 74) persuasively argues that today, ‘the term “professional” refers more to a prescribed attitude toward work than the status of some work’. According to Foucault, ‘professionalism is in itself “a disciplinary mechanism”; associating specific practices with particular worker identities, knowledge and rules of conduct thus legitimising professional authority and activity’ (Powell and Khan, 2012: 137).

Conceptually, I take my analytical cue from some of the work of Bourdieu and Wacqaunt. According to these French sociologists, a number of previously autonomous or quasi-autonomous ‘fields’, such as social work, are becoming contaminated and corroded by neoliberal imperatives. Thus, the transformation from ‘field’ to ‘apparatus’ occurs when ‘under certain historical conditions’ all movement and decision-making ‘go exclusively from the top down’ (Bourdieu in Bourdieu and Wacquant, 2004: 102). In other words, increasingly denuded of democracy and a commitment to their original mission, apparatuses are ‘the pathological state of fields’ (Bourdieu in Bourdieu and Wacquant, 2004: 102, emphasis added). Given this situation, Wacquant (2009: 285) argues that it is vital for ‘agents of the state’ to continue to ‘defend the dignity and integrity of their occupations and refuse to let themselves be roped into assuming degraded versions of social and health functions that do not properly fall to them’. Within this conceptual framing, therefore, ‘professionalism’ can be viewed as the managerial ideology of the social work ‘apparatus’ which amplifies ‘degraded’ versions of practitioner roles. Thus, the Irish ‘Social Workers Registration Board Code of Professional Conduct and Ethics’, which deleted the phrase ‘human rights’ form its text, can be perceived as a product of the ‘apparatus’ as opposed to the ‘field’. Expressed in a rather crude and banal way, the ‘professionalism’ of the social work ‘apparatus’ is one that is likely to become more concerned about a social worker allegedly violating the office ‘dress code’ than it will be about, say, a homeless young man compelled to spend his nights sleeping in a tent adjacent to the office car-park.

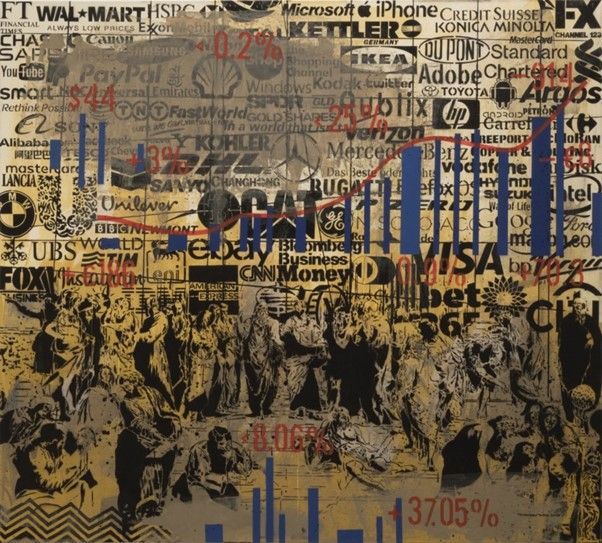

Farhan Siki (Indonesia), Market Review on School of Athens, 2018.

Dissent is, of course, fraught with conceptual difficulties and half-a-dozen issues can be by briefly mentioned. First, the purpose of dissent and its desired outcome is of the utmost significance. That is to say, dissent, as theory, disposition and oppositional practice, should not be fetishised or unequivocally supported and valorised. For example, largely against the political and corporate mainstream that at least rhetorically espouse the value of racial equality, white supremacists are dissenters because they are unequivocally opposed to it. Bailey (2020) challenges the notion that protest should simply be seen as the ‘preserve of progressive causes’. DSW, therefore, champion forms of dissent adhering to the values featured in the IFSW definition; important here is the reference to social work being a part of the struggles aspiring to bring about the ‘liberation of people’ whilst adhering to the principles of social justice and human rights. Historically, such struggles have often been housed within encompassing projects intent on creating communist or socialist societies.

Second, occasionally what might appear to be dissent might paradoxically be understood as an expression of a ‘higher’ and more substantial form of consent-giving and compliance. For example, in Ireland it might be argued that some social workers’ opposition to the extinguishing of the phrase ‘human rights’ in the dismal and degraded Social Workers Registration Board Code of Professional Ethics (CORU, 2019), represents less a form of dissent and more a form of allegiance to the IFSW definition of social work. This fidelity to the international definition might also be founded on the belief that the Irish Code, not voted on and agreed by practitioners in Ireland, is entirely bereft of even a scintilla of democratic legitimacy.

Third, dissent and social critique are always vulnerable to becoming diluted and incorporated into the mainstream: words and concepts can be slyly abducted and taken to places they are not supposed to be taken! The difficulty we face, as Fisher’s (2009) ‘capitalist realism’ notion makes plain, is the tremendously absorbent character of the extant hegemonic apparatuses. The Chilean feminist collective LasTesis (2023: 20-21) stress:

Capitalism possesses the brutal capacity to take ownership of everything. Even critiques of capitalism end up processed, re-appropriated, defanged as tools of struggle, and turned into consumer goods, commodities of the market. One of capitalism’s survival mechanisms to sustain its hegemony, is to absorb strategies of resistance. It absorbs them, wrings them out.

In their research on management literature from the 1960s and early 1990s, Luc Boltanski and Eve Chiapello (2005) reveal that managerial ideology is heavily indebted to the anti-capitalist discourse of the 1960s. Writing prior to the economic crash of 2007/8, they identify a ‘new spirit’ of capitalism better able to attract support and more inclined to encompass the themes of justice and social well-being. Unable to discover ‘a moral basis in the logic of the insatiable accumulation process (which, in itself, is amoral), capitalism must borrow the legitimating principles’ that are ‘external to it’ (Boltanski and Chiapello, 2005: 487). Occasionally, such banditry is starkly opportunistic and cynical with one of the prime examples being Trowler and Goodman’s (2012) UK Conservative Party supported ‘reform’ programme using the banner Social Work Reclaimed despite their aims being radically at odds with Ferguson’s (2008), anti-neoliberal and social justice driven, Reclaiming Social Work. However, such tactics reflect Stuart Hall’s (2017 [1958]) sixty-year old insight that in the ‘subtlest and more complicated ways’, capitalism and its allies recognise and try to address, at least in some form, the ‘human problems’ that in ‘substance socialism first named’.

Ecological movements and a new green sensibility also impact on the evolution of this ‘new spirit’ in that nature is now accorded value as ‘the locus of the authentic’ (Boltanski and Chiapello, 2005: 447). At the forefront, in creating new ‘greenwashing’ narratives, tend to be multinational corporations still mired in the fossil fuel economy. For example, ‘BP is not the first oil company to give itself a lick of green paint to appear more acceptable in this era of increasing climate concern’ (Bell, 2020). As we can see, therefore, dissent and critique are often reformulated to try and revitalise the processes of capital accumulation and the social order conducive to its maintenance. Demonstrations of ‘resistance’ are prone to becoming ‘captured – with ever-growing intellectual violence – by grids of interpretation that cancel or recode them in the categories of dominant thought’ (Rancière, 2014 [2009]: xi). Relatedly, Nancy Fraser (2013: 220) asserts that dissenting ‘second-wave feminism has unwittingly provided a key ingredient of the new spirit of neoliberalism’.

Fourth, there is a need to think about the differential positionality and, after Bourdieu, the ‘habitus’ and ‘field’ location of the agent of dissent, the dissenter. For example, within the field of social work, not every worker will, of course, exhibit dissent in the same way. For example, a middle-aged, white male academic in unionised, seemingly secure and pensionable employment, has, perhaps, greater leeway to shape dissenting practice than, say, a newly qualified – most likely female – social worker employed by an agency on a temporary and precarious contract. Significantly, Black and ethnic minority social workers are over-represented in ‘fitness to practice’ cases adjudicated on by the Social Work England regulatory authority (Samuel, 2020). There is also, of course, a material base governing one’s consideration of whether or not to express and act on dissent. In short, in some instances, there may be fear of losing one’s job or of becoming ostracised or bullied in a particular office or work environment. Many students now enter their first social work job weighed down by debts incurred because of college tuition fees and the exorbitant rents demanded by rapacious landlords. Whilst teaching at public universities, as far apart as Galway and New York, I have spoken with students who are literally homeless. Clearly, debt and related problems might tip the potential dissenter to act, but it might also materially coerce them into grudging compliance.

Fifth, sometimes the language of dissent may be culturally variable and those of us in the Global North need to recognise that the dissenting vocabulary of activists in the Global South may be different (Shahid and Jha, 2014; Muñoz Arce, 2018; Muñoz Arce and Duboy Luengo, 2023). The Eurocentric critical tradition needs to become better attuned to the fact that oppositional practices may circulate around historically and culturally embedded ideas relating to, for example, defending ‘good living, and mother earth’ (see also Marovatsanga and Garrett, 2022). Relatedly, the Indian historian Dipesh Chakrabarty (2000: xiii), in endeavouring to ‘provincialise’ Europe, notes that European ideas often purporting to be universal are, in truth, drawn from very particular intellectual and historical traditions’ that may lack ‘universal validity’. Abhijeet Mishra (2023a; 2023b) has explored this dimension by dwelling on the history of social work education in India. Such perceptions have resonance in terms of how we think about dissent and about quotidian facets of social work practice.

Sixth, it is vital that dissent becomes organised and collectivised as opposed to it being a singular endeavour. Foucault claims that ‘we are all members of the community of the governed’ and so are ‘obliged to show mutual solidarity’ with those subjected to maltreatment by the state. Hence, there has to be a preparedness to ‘stand up and speak to those who hold power’ (Foucault, 2002: 475). His perceptions are underpinned by an intellectual interest in parrhesia (Foucault, 2015): derived from Greek antiquity, this is founded on the idea of ‘fearless speech’ and the need to speak the truth to power (Christie and Sidhu, 2006). However, the perceptions of Marston and McDonald (2012), related to assessing the scope for dissent, remain important. For them, there is a problem with the tendency to issue ‘heroic’ claims about ‘what social workers can achieve in the name of empowerment and social justice’. Thus, ‘emerging practitioners should be supported to develop greater clarity about what they can and cannot do in the context of twenty-first-century spaces of social work practice’ (Marston, and McDonald, 2012: 1024). ‘Grand’ or ‘heroic’ thinking is inclined to emphasise the ‘triumph of agency over structure’ and it can achieve little other than, perhaps, burnout or the creation of a few ‘heroic’ martyrs (Marston and McDonald, 2012: 1025-6). Workplaces can be places of great and tenacious solidarity, but they can also be tough locations in which questioning, but isolated individuals, can be subjected to intimidation and legal sanction. Arguably, recent developments, such as mandatory professional registration may also engender a certain nervousness inhibiting dissenting and critical thought and practice. That is why endeavours to promote social change have to been wedded to collective projects democratically charted by organisations and the ‘resistant experiences’ and ‘resistant imaginations’ of trade union networks and other progressive social movements (Medina, 2013: 7). Expressed slight differently, dissenters must aspire to ‘win’ and not merely to ‘virtue signal’. Thus, key questions become: what are the opportunities for dissent in a specific domain (nationally, regionally, locally and in terms of practice specialism) at a particular conjuncture? What are the obstacles? How can these obstacles be challenged by the creation of oppositional, dissenting alliances? Workers need to collectivise their discontent and aspirations by, to use Marx’s (1990 [1867]: 416) phrase, putting their ‘heads together’. Indeed, the ‘collective labourer’ or ‘combined working personnel’ is a force which has the potential to challenge and eradicate oppressive practices (Marx, 1990 [1867]: 590).

References

Bailey, D. J. (2020). ‘Decade of dissent’, The Conversation, 3 January http://theconversation.com/decade-of-dissent-how-protest-is-shaking-the-uk-and-why-its-likely-to-continue-125843

Bell, A. (2020). ‘Beware oil execs in environmentalists’ clothing – BP could derail real change’, The Guardian, 14 February https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2020/feb/14/oil-execs-environmentalists-bp-change-oil-climate

Boltanski, L. and Chiapello, E. (2005). The new spirit of capitalism. London: Verso.

Bourdieu, P. and Wacquant, L. J. D. (2004). An invitation to reflexive sociology. Cambridge: Polity.

Chakrabarty, D. (2000). Provincializing Europe. Princeton University: New Jersey.

Christie, P. and Sidhu, R. (2006). ‘Governmentality and ‘fearless speech’, Oxford Review of Education, 32: 449–465.

Cooper, S. (1977). ‘Social work: a dissenting profession’, Social Work, 22(5): 360-367.

CORU (2019). Social Workers Registration Board Code of Professional Ethics

Ferguson I. (2008). Reclaiming Social Work: Challenging Neoliberalism and Promoting Social Justice. SAGE: London.

Fisher, M. (2009). Capitalist realism. Winchester: O Books.

Foucault, M. (2002). ‘Confronting governments: human rights’. In J. D. Faubion (ed.) Power: Essential works of Foucault, 1954–1984 (Vol. 3). London: Penguin, pp. 474–476.

Foucault, M. (2015). The punitive society. Houndmills, UK: Palgrave Macmillan

Fraser, N. (2013). Fortunes of feminism. London: Verso.

Fronek, P. and Chester, P. (2016). ‘Moral Outrage: social workers in the Third Space, Ethics and Social Welfare’, 10(2): 163-176.

Garrett, P. M. (2018). Welfare Words: Critical Social Work and Social Policy. London: SAGE.

Hall, S. (2017 [1958]). ‘A sense of classlessness – 1958’. In S. Davidson, E. Featherstone and B. Schwarz (eds.) Stuart Hall: Selected Political Writings. Durham, US: Duke University.

Marovatsanga W. and Garrett, P. M. (2022). Social work with the Black African diaspora. Bristol: Bristol University Press.

Marston, G. and McDonald, C. (2012). ‘Getting beyond ‘Heroic Agency’ in Conceptualising Social Workers as Policy Actors in the Twenty-First Century’, British Journal of Social Work, 42: 1022-1038.

Marx, K. (1981 [1857-58]). Grundrisse. London: Penguin.

Marx, K. (1990 [1867]). Capital, Volume 1, London: Penguin.

Medina, J. (2013). The Epistemology of Resistance. Oxford: Oxford University.

Mishra, A. (2023a). ‘Imperial entanglements of modern social work education in India’, Social Work Education, 42 (4): 476-493.

Mishra, A. (2023b). ‘Professionalization of social work in colonial India: Glancing at the history of social work in India before 1936’, International Social Work, 66 (4): 1018–1029.

Muñoz Arce, G. (2018). ‘Critical social work and the promotion of citizenship in Chile’, International Social Work, 61(6): 781-793.

Muñoz Arce, G. and Duboy Luengo, M. (2023). 'Decolonial Feminism and Practices of Resistance to Sustain Life', Affilia, DOI: 10.1177/08861099221148155.

Palmer, B. (2023). ‘Hero from Capitalism’s Hell’, New Left Review, 139: 45-105.

Powell, J. L. and Khan, H. T. A. (2012). ‘Foucault, Social Theory and Social Work’, Sociologie Românească, 10(1): 131-147.

Rancière, J. (2014 [2009]). Moments Politiques. New York: Seven Stories Press.

Samuel, M. (2020). ‘Black and ethnic minority social workers disproportionately subject to fitness to practise investigations’, Community Care, 31 July https://www.communitycare.co.uk/2020/07/31/black-ethnic-minority-social-workers-disproportionately-subject-fitness-practise-investigations/

Shahid, M. and Jha, M. K. (2014). ‘Revisiting the Client-Worker Relationship: Biestek Through a Gramscian Gaze’, Journal of Progressive Services, 25: 18-36.

Trowler I. and Goodman S. (2012). Social Work Reclaimed. Jessica Kingsley: London.

Wacquant, L. (2009). Punishing the Poor. Durham & London: Duke University.

Weeks, K. (2011). The problem of work. Durham & London: Duke University.